Now that the blog has been up for a week you’re probably looking between Instagram and this blog going, “Okay lady, where’s the goods? I got the ‘Reads’, where’s the ‘Tea’?” Fair enough. I’ve focused a lot on the books and reading portion of this blog. It’s time we took a closer look at some tea.

The question I’m asking in the title may sound silly, especially if you’re someone who drinks tea regularly. What is tea? Well, duh. It’s my chai lattes from Starbucks. It’s the boxes of tea bags with cuddly bears or idyllic English countrysides on the packaging. It’s the iced tea I make to drink on my porch in the summer. Right?

To start this discussion, we have to talk a little about the etymology of the word “tea”. The English word “tea” can be traced back to the Chinese word 茶, pronounced “teh”, “té”, “tu”, or “cha” depending on the region. This word referred specifically to a beverage made from the buds and leaves of the Camellia sinensis tree and hot or boiling water. The Camellia sinensis was important in China- the creation of tea had already passed into the realm of legend by the time China was trading it in bricks along the Silk Road. It’s also notable that, until the 19th century, no other country had ever found or grown the Camellia sinensis.

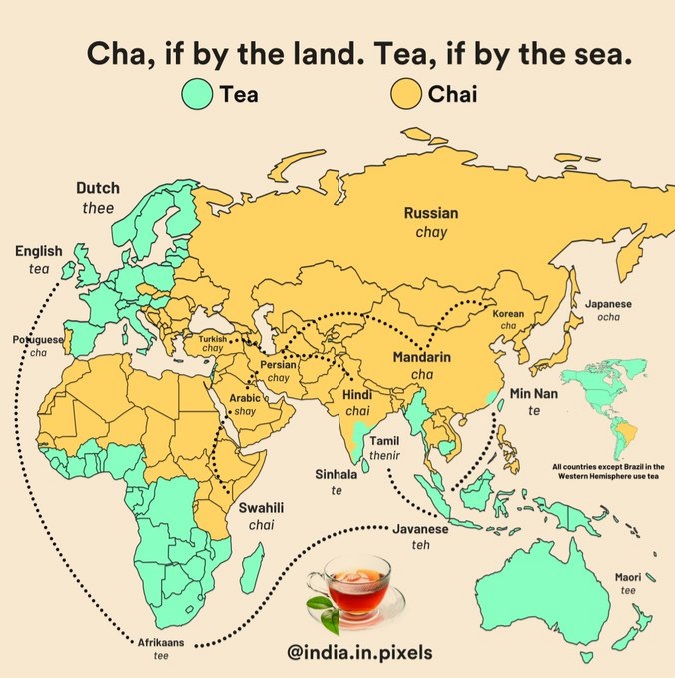

Chinese tea culture spread through many of the surrounding countries, whether through the Silk Road or the various ports on China’s coast. The word 茶 began to travel to different languages, different dialects and branched in two distinct ways on its travels. If tea was being traded overland towards Persia, it often went by the pronunciation “cha”. This eventually played the game of Language Telephone and became “chai” (y’know, one of the most popular forms of drinking tea in the world. Thank India and the Middle East for your chai latte next time you’re at Starbucks). Along the coast, specifically near Fujian, China, tea traded through the ports went by the pronunciation “teh” or “té”. It’s believed that Dutch traders were the ones who brought the word back from Fujian, and over time evolved into our current word, “tea”.

Infographic by India.In.Pixels on Instagram (used with permission)

All that information is important to our definition of what tea is, I promise. You may have noticed that I mentioned that the Camellia sinensis tree did not exist outside of China, and didn’t for most of recorded human history. The history of the very word we use comes from the Chinese word for the beverage they made from that tree. It follows, then, that the strictest definition of tea is any beverage that is made from the buds and leaves of the Camellia sinensis. This encompasses a lot more tea than you think- any time you drink a black tea, a green tea, or a white tea, you’re drinking our bud Camellia. The tea tree is also responsible for all oolongs, yellow teas, pu-er teas, and matcha. The tea doesn’t have to be pure Camellia either- your chai latte or your Earl Gray lavender still counts as tea. You could have one tea leaf and a bunch of chocolate chips in your infuser and still consider the outcome to be tea (though I might have some questions).

Whew. All that just to define tea. But now we have to look at the flip side- what isn’t tea? If you’ve been reading this and thinking about your favorite sleepy-time chamomile tea and wondering where it fits in, well, we’re there.

After the word “tea” entered our lexicon, we started calling anything we steeped the same way as we steeped tea leaves, “tea”. Humans like to categorize things. If both my tea leaves and my chamomile flowers come in tea bags and get steeped in hot water, aren’t they The Same? “Tea” became shorthand for “Plants Steeped in Hot Water” and now many herbal infusions (also called tisanes by fancy people) are marketed as tea. Is this wrong? Is this right? Has language devolved and we’re all going to become illiterate fools who speak in abbreviations? Idk.

Joking aside, the answer is no. Let’s look at our friend the tomato as a guide. Tomatoes, botanically, are a fruit. Technically a berry. We as a society have largely rejected that (and so has the Supreme Court! Check out Nix v. Hedden, 1893). The flavor profile of tomato does not fit what we, in a culinary sense, consider a fruit. You don’t put tomatoes in a fruit salad. So we’ve thrown it in with the veggies and ignore the botanical classification. It’s not the only fruit we’ve done this to- bell peppers and cucumbers are also part of the Fruit-We-Decided-Are-Vegetables Club.

Applying that same logic to tea, yeah, chamomile isn’t tea. It’s the chamomile flowers and buds, no Camellia sinensis to be found. Rooibos tea? That’s Aspalathus linearis, no relation to Camellia. No matter how many fun plants you throw in a teabag, it doesn’t, by the strictest standard, make it tea. But, much like how a tomato is a fruit, do we care?

Language is constantly evolving. While I find the specificity of language incredibly important when writing, I don’t think we should be gatekeeping entire hobbies from people because of some word choice. If I’m writing an informational post about tea, I’ll go ahead and distinguish non-tea blends as tisanes, but if I’m talking to my partner or my friend about some Egyptian Chamomile I just bought, I’m going to shorthand it to “tea” because, frankly, who cares. The world of tea has so many fun things to try, why fight over the right word for some hot plant water?

My point is this: Tea is a beverage made from the leaves of the Camellia sinensis. It’s also turned into shorthand for a drink made from steeping plants in water. If a tea purist is standing on the corner of an intersection with one of those big sandwich boards saying “Tisane Drinkers Go To Hell” or something, ignore them. Or, better yet, ask them if the tomato is a fruit or vegetable. Watch them squirm.

If you’d like to read more, the information I used to create this article came from:

Quartz, “Tea if by sea, cha if by land: Why the world only has two words for tea” by Nikhil Sonnad

Online Etymology Dictionary, “Etymology of chai.” Harper, Douglas.

Kevin Gascoyne, Francois Marchand, Jasmin Desharnais and Hugo Americi, Tea: History, Terroirs, Varieties, First Edition (While the first edition is no longer for sale, updated editions may be found at your local bookstore or places like Barnes & Noble)

2 thoughts on “What Is Tea?”