There’s a big rivalry in the tea world. It’s on par with the Chicago Bears and the Green Bay Packers; the Rock and Stone Cold Steve Austin; Goku and Vegeta. While the tea community prides itself on its “chill” status, the mere mention of the rivalry can send even the most zen tea connoisseur into a rant. Tea drinkers pull out statistics, objective strengths, and weaknesses tinged with defensiveness. The battle rages quietly on, cage matches held in passive-aggressive looks and rolled eyes. It’s the headliner and the rivalry no one wanted: Tea Bags versus Loose Leaf.

While I’d pay money to see a Loose Leaf Drinker come flying into the ring with a steel chair, that’s not how this rivalry plays out. Tea bags dominate the market, with 51% of tea-drinking Americans exclusively drinking tea made with tea bags and 20% saying they mostly use tea bags. A study in 2007 found that, of all the tea consumed in the UK, 96% of it was made with tea bags. If we look at the market, the tea bag has already won. When people look to expand their tea horizons, they bump up against the more niche loose leaf tea market with its unique vocabulary, special brewing methods, and terroirs to learn (and maybe a bit of snobbery. No hate, just sayin’). The differences can be overwhelming. To help those starting on their tea journey, I want to take the time to lay out the differences between tea bags and loose leaf tea, illuminating a rivalry a hundred years in the making.

Tea bags are a relatively recent invention. Since the beginning of their trade with Europe, China had always supplied tea in bricks, cakes, or loose. The vessels for steeping, from gaiwans to teapots, were made with loose leaf tea in mind. As time went on, most major tea trade was in loose leaf, often with terroir and cultivars an important part of marketing. There were few exceptions.

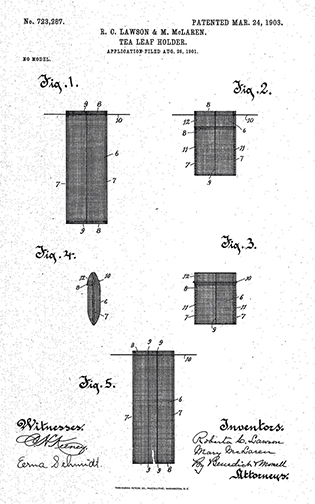

Around the turn of the twentieth century, patents began appearing in the US for mesh bags to hold tea leaves. One notable example is the patent filed in 1901 for a fabric mesh Tea Leaf Holder by Roberta Lawson and Mary McLaren of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Thomas Sullivan, often credited with the invention of the tea bag, didn’t send out tea in silk sample pouches to his customers until 1904. As more designs entered the market, Americans found the ease of steeping in bags and the economical advantages of using less tea per steep were preferable to loose leaf. Tea bags began overtaking the loose leaf market.

Image Credit: Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum (link at end of post)

Expanding consumer demand and traditional tea leaf processing don’t mix well. The hand-picking, the long drying times, the differences in taste depending on region- it didn’t fit with the burgeoning industrialization of agriculture. That’s why, in 1930’s India (one of the biggest suppliers of tea for Europe), the CTC method took over. The process took whole tea leaves and Crush, Tore, and Curled them into smaller bits. This led to smaller leaves to fit in tea bags and more salable tea per harvest. It also took leaves from several different harvests to process at once, leading to a consistent and stable flavor throughout the entire end product. Most modern tea bags are made with the CTC method to this day.

Just by learning the history between the two bitter rivals, you can already see some of the major differences between loose leaf teas and tea bags, namely the leaf size and processing methods. These two differences may not seem like much but they both drastically alter the result, leading to a rivalry for the ages. The gloves are on. The opponents are squared up. Let’s get ready to rumble.

The biggest difference between loose leaf teas and tea bags is the size of the leaf. Loose leaf teas are graded by the size of their leaves, usually falling into two categories: whole-leaf and broken-leaf. These grades are self-explanatory: Whole-leaf tea means the entire leaf is supplied, while broken-leaf tea has mostly whole leaves, though some may have broken during processing. Tea bags, on the other hand, are made of fannings and dust. Tea fannings are broken leaves that are too small to be placed in the higher-grade broken-leaf category. Dust is exactly as it sounds: the tiny particles left over after processing the tea. Both fannings and dust are usually created through the CTC method, though sometimes tea bags may be made with the leftovers of higher-grade teas after the whole- or broken-leaves have been separated and processed.

Leaf size may seem like a small difference, but it has big effects. Since tea bags are made of such smaller leaves, they have a higher surface area ratio, meaning more of the leaf is exposed to the air than not. This oxidizes the leaf faster, leading to the tea bags on your shelf going stale (yes, tea can go stale! Consider that the next time you’re cleaning out your pantry!). Oxidation also impacts taste- higher oxidation leads to stronger, more astringent, or bitter flavors, which is why the majority of tea bags on the market are for black tea. If you’re drinking tea for the potential health benefits, leaf size also plays a role. Smaller, highly oxidized leaves mean a lower concentration of the antioxidants found in tea end up in your cup.

Loose leaf teas, with their smaller surface area ratio, keep most of their Yummy Tea Chemicals intact. As they unfurl in the pot, they release all the flavonoids and antioxidants they’ve been storing, leading to improved levels of Good Stuff released in your cup and more varied flavors. They also oxidize slower, meaning that loose leaf teas will keep fresh longer. Some of the benefits of loose leaf can flip the other way, however- If you like a consistent flavor and product, taking a chance on loose leaf can be a little more difficult. Ordering Dragonwell tea from two different websites can lead to two different cultivars, terroirs, and flavors. Loose leaf tea keeps all the aspects of how it’s grown, meaning product can vary wildly from the first flush to the last flush.

While most of the rivalry stems from the facts above, there’s one that often gets left out of the conversation: accessibility. Let’s get real, my fellow loose leaf tea snobs. Tea bags are cheaper, more convenient, and don’t require any investment. For the average person who wants to cut their caffeine intake or doesn’t like the taste of coffee, tea bags make way more sense than dropping money on a kettle with temperature control, a teapot with a strainer or a built-in steeper, or a few stand-alone infusers. That doesn’t even touch on the higher price-point for loose leaf teas, when, realistically, they make fewer cups than a box of tea bags. Don’t get me wrong, I’m loose leaf tea all day, but we need to admit where it falls short.

Companies are attempting to bridge the gap between the two rivals. Some tea shops now sell what they call tea sachets. Sachets are larger, often pyramid-shaped tea bags that can fit whole- or broken-leaves inside and allow them enough room to unfurl. This gives you the best of both worlds- the ease of a tea bag but the quality of loose leaf. You can also buy your own sachets but that does add labor on the tea drinker’s part, which can defeat the whole point of using a tea bag.

At the end of the day, these two rivals can only fight so long. The tea community shouldn’t be about how you’re consuming tea; what might work for some won’t always be available for others. So so so many people begin their tea journey with tea bags. Why should we condemn them, or those who never venture further? It weakens the community and the variety of experiences. After all, we have more in common than we think. Whether you’re Team Tea Bag or Team Loose Leaf, we can all agree: tea is pretty damn good.

The sources I used for this post are below: Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum, "Who Invented the Teabag?" Alexander Kunst, Statista, "Preference for Tea bags or Loose Tea in US 2019" Kevin Gascoyne, Francois Marchand, Jasmin Desharnais and Hugo Americi, Tea: History, Terroirs, Varieties, First Edition (While the first edition is no longer for sale, updated editions may be found at your local bookstore or places like Barnes & Noble)