About halfway through Americanah, we see the origin of Ifemelu’s blog, “Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black”. She makes her first post and checks the stats a little later. Nine people have read it. She panics and takes the post down, editing and modifying it to repost the next morning. That primal panic, that “Oh no, someone’s actually reading this,” feeling is one many bloggers can relate to. I can’t count how many times I’ve wanted to take a blog down or felt nervous about how a post might be received- this one included.

Here’s why: I wasn’t a fan of Americanah.

While you all grab your pitchforks and spoiled vegetables, remember that taste does not directly correlate to quality. Just because I didn’t like the book doesn’t mean I don’t see its artistic value. We all have preferences and, despite it not matching many of mine, I cannot dismiss some of its strongest qualities.

A primarily character-driven novel, Americanah tells the tale of two high-school sweethearts from Nigeria. It charts the journeys of Ifemelu and Obinze from teens to adults and their respective immigration to America and Britain. Both characters navigate the concept of race, immigration systems, and relationships abroad and at home. Ifemelu takes center stage for most of the book, many of her experiences with race and American culture pulled from author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s own life. The book comes together as a social commentary, Adichie’s sharp prose and character vignettes cutting issues down to the quick.

The pointed language of these vignettes and their careful, nonlinear construction is one of the best parts of the book. Adichie’s gift for observational storytelling is a perfect pairing for Ifemelu, who makes a career out of observations of others for her blog. Her sentences are piercing and witty, and scenes are stitched together to evoke a point, leaping forward or back in time for needed context. Combining those scenes with Ifemelu’s shorter, more conversational blog posts makes the book feel well-rounded and whole.

Adichie’s style is great for making smart political commentary. She touches on many subjects regarding race, from social and economic class to natural hair. My favorite, and what I found the most unique, were the sections where she skewered the white American liberal. So many books that deal with race in America focus on outward racists, the American Conservatives, or WASPs (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants). Since the Venn Diagram of these three categories is practically a circle, it makes sense to focus on them. They’re the most damaging. Still, it’s interesting that I’ve read very few books that look at the passivity or internalized racism inherent in the white liberal. I laughed at the sections with Kimberly, who calls every black person “beautiful” regardless of their appearance, or Blaine’s friend Stirling who, so weighed down by his privilege, refuses to have an opinion. It was refreshing, even in a book from 2013, to have it discussed with the same shrewd language as the rest of the book. It’s good to eat some humble pie now and again.

Even when an entire chapter isn’t dedicated to a cultural critique, there are still some quieter criticisms that sneak in. These subtle, sentence-or-two, bits of scrutiny caught my attention more than the overt commentary did. The biggest one is the word “Americanah”. In Nigeria, it’s what you might call someone when they come back from America with American attitudes, preferences, and complaints. It’s meant as playful ribbing for the most part, laughing at friends’ new accents or their love of air conditioning. Yet throughout the book, Adichie peppers in little details: How Obinze loved watching The Cosby Show and reading American novels; how all the popular kids in class traveled to the UK or the US; how well-to-do mothers sent their children to French-run schools, where the school’s Christmas play featured snow. The slow, creeping overtake of culture isn’t something Ifemelu directly writes or complains about- the cultural erosion at the hands of colonialism has affected her, too.

With all this praise I’m lavishing, it’s hard to believe I have such a dislike for Americanah, but all the delightful commentary and its fantastic execution couldn’t save my feelings towards the characters or the ending. That said, I can’t discuss those bits without spoilers. I hate to leave it there for those still on the fence about reading it, so let me say this: When weighing the parts I found insightful against the parts that made me bang my head against a wall, the head-banging won out. I can only take so much before wondering if I’ve been concussed.

Would I recommend this book? Probably not. I think it’s a good character study that dives into some interesting topics, but it’s not worth the 600-page slog. Again, that’s just my taste- your mileage may vary.

If you’ve read the book and want to listen to me gripe about what I didn’t like, feel free to scroll down to the Spoiler Section! If that doesn’t sound like the right thing for you, I’ll see you next week for our introduction to September’s Book of the Month. Happy reading!

The reflection above is intended for people who have not read or completed the book. For that reason, it is spoiler-free. The following section is going to discuss plot points in the book not otherwise described in the summary or book blurb. That means there are SPOILERS BELOW. This is your warning.

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

LAST CHANCE! SPOILERS AHOY!

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

In my introduction to Americanah, I joked about being burned like I had been with Conversations With Friends. Both were lauded by critics and the public alike, and both were famous enough to land TV deals. I wanted to be wrong about that joke. In a cruel twist of fate, I found myself burned the same way for a second time.

Ifemelu’s characterization is well done. From a young age, she’s headstrong and observant, two traits that grow and morph as she ages and immigrates. What starts as a gift for observation sours into judgment. Her headstrong behavior never wavers, instead becoming more solidified as her opinions are bolstered by the popularity of her blog. By the end of the book, she is surprised when her judgemental nature turns people against her. When she cheats on Curt and he calls her a bitch, she can’t believe he could even say that to her. When she snaps at Doris and Doris starts screaming at her, Ifemelu, shamed by the exchange, barely even registers it as her fault. Instead, she wonders if Doris was “one of those women who could transform when provoked, and tear off their clothes and fight in the street”. She lacks so much self-awareness that she can’t see the root of her issues: herself.

This may make an interesting character, but it’s not a character I want to follow for 600 pages. Every page is an interesting examination of culture served alongside a heaping helping of judgment. I often found myself having to reread parts that contained a hilarious lambasting of cultural norms because I’d been distracted by the backdrop of Ifemelu being rude to, well, everyone. The people she dates are rarely talked about in a positive light. Friends of friends, or worse, strangers, are subject to harsh spotlights where any quirk is a reason to make fun. Reading the book became like talking to that one friend we all have that does nothing but complain. It was exhausting.

For a while, though, I had hope. Her dismissiveness about depression in the first half of the book had me wondering if we would see her unpack her trauma and realize her self-righteousness might be a defense mechanism. When Dike attempted suicide in the last hundred pages, I hoped this was the catalyst for Ifemelu to take her mental health seriously or reflect on her actions and words. Instead, it went nowhere. Ifemelu didn’t change in that regard.

Americanah’s loose plot threads don’t stop at Ifemelu’s depression or Dike’s suicide. Other plot points, like Ifemelu’s relationship with her parents or Obinze’s American Dream, are abandoned. Hell, even the thread between Ifemelu and Obinze stood frayed at the end, left unresolved with the door, literally and figuratively, open. With a book as big as this with so much to say, it might’ve spared a moment for mental health or a resolved ending.

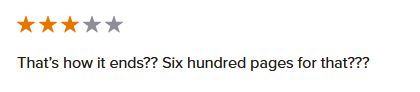

These may seem like relatively minor gripes, but, as a whole, they took up a large chunk of the narrative. Ifemelu exhausted me, Obinze wasn’t much better, and there were so many plot lines that were started that I would’ve liked to see resolved that when I read the last line, I was annoyed. As my favorite Goodreads review says:

Here’s hoping for something a little more up my alley in September. See you then!