If you’ve been following the Writing Rules series, you might have clicked on this blog post with some skepticism. Every “rule” so far has been a phrase, something catchy to teach new writers a simple trick to improve their prose. This rule is a little different; instead of one writing “rule” to pick apart, there are several. So many that I can’t even count them all. Today we’re talking about grammar.

Grammar is every rule about punctuation. Every rule about sentence structure. All the rules about phrasing, word choice, and paragraph breaks. Anything and everything that dictates how we write is grammar. Put them all together, and you have a Bag of Writing Rules bursting at the seams with systems and structures of languages, comma splices leaking out and dripping onto the floor. I could pull each rule out, one by one, and write an essay-length blog post explaining them all. Hell, I should. I’d never run out of content. But the blog posts would be boring, bone-dry theory, no matter how much humor I attempted to inject. Rather than subject you to that, I thought it best to treat grammar in a gestalt fashion– looking at the whole instead of the parts.

Regardless of the dread that wells within our souls when we hear someone start to talk about prepositions or declaratives, our day-to-day lives wouldn’t exist without systems of grammar. Many of us may not even notice it. The structure of our sentences, the phrasing, and the tones we use to talk to our friends all use grammar that we learned passively while growing up. It’s only when it comes time to translate those words onto paper do the rules trip us up. We have to learn how to convert breaths into commas or different pauses into punctuation. It’s hard, but when everyone who speaks a language knows the same basic rules it ensures that any piece of writing can be read. Grammar is language and language is grammar. There’s no untangling the two.

Grammar is one writing “rule” you can’t skip past on your way to authordom. Writing that doesn’t follow the rules of grammar is difficult to understand, sometimes incomprehensible. If your reader opens your book and finds that they are spending more time deciphering what you’re trying to say instead of being immersed in what you’re saying, the chances of them reading to the end are zero. Bad grammar can confuse action, intention, and immersion.

Let’s take this example:

todd was a wearwolf and he could see the moon hanged in the sky like a white big disc and he knows its time. he had fur popping out and their was sharp noise as his bones breaked and reset into their new shapes and he could smell everything everywhere the mice the neighbors the candy shop down the street he could smell it all and it is delicious he wanted some real bad so he waited for his nails to grow and his hare to cover his body and then he went out in the night to find something to eat. he is really hungry!!!

All the broken rules destroy readability. Every sentence requires mental rearrangement to understand (did you catch yourself replacing “white big” with “big white” in your head?). The run-on sentences and a lack of punctuation make the entire paragraph read like a toddler trying to tell you an exciting story in one breath. While the example is extreme, even minor errors like speling mistakes and incorrect, comma, placement, can stick out like sore thumbs.

At the end of the day, the point of good grammar is for it to become invisible. You don’t want readers to notice your punctuation or sentence structure, you want them to be immersed in your work. It’s why good grammar is so important and bad grammar is so reviled. One allows the reader to access whole worlds of enjoyment; the other is a locked door, barring any entry into the imagination.

For those of you who, like me, have a decent grasp of grammar but struggle against one or two rules, there is hope: online grammar tools. Websites like Hemingway or Grammarly (the two I use most frequently) are there to highlight your complex sentences, inappropriate commas, and absent particles. There is some basic grammar knowledge required– robots are smart, but they do flag things incorrectly from time to time– but these tools are there to ensure that anything you put out into the world follows as many grammar rules as possible. Use them.

With how vehemently I’ve argued for all of you to study your grammar guides, you’ve got to be wondering: can you break grammar writing “rules”? Wouldn’t breaking those rules make your work unclear or make the grammar stick out on the page, breaking reader immersion? Well. Here’s where it gets tricky. You can break grammar rules for one reason and one reason only: style.

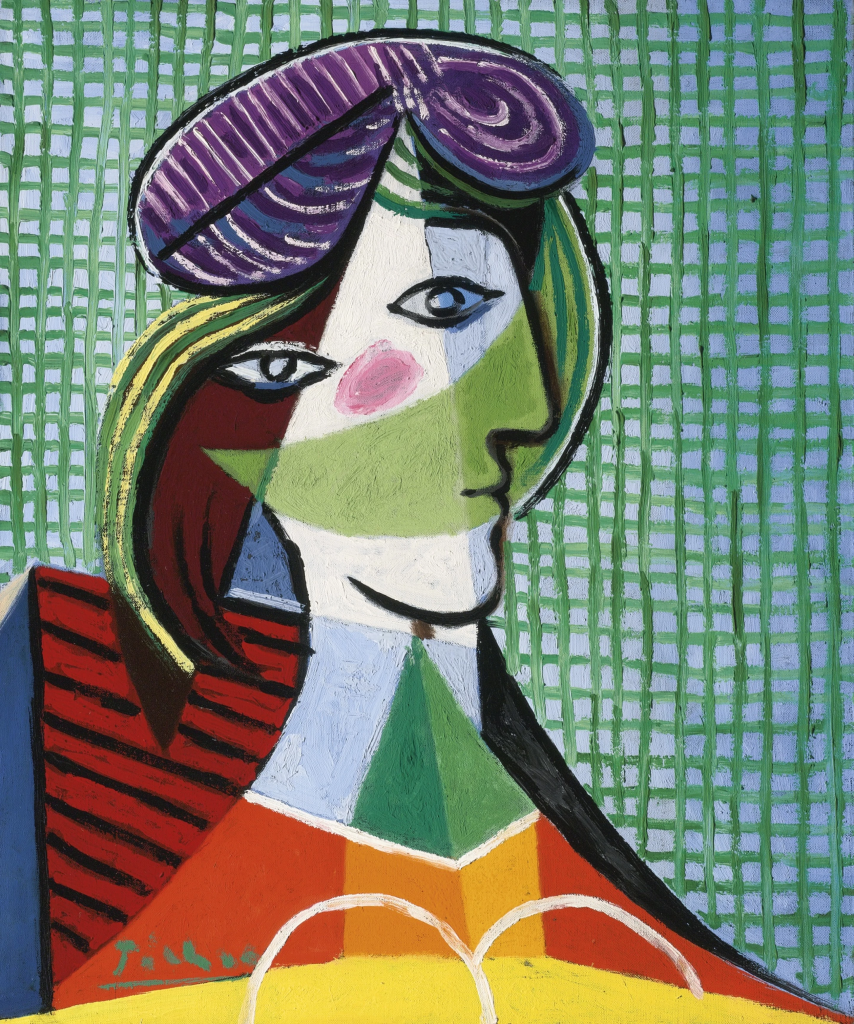

When you take a beginner’s art class, for example, the teacher doesn’t let you start by creating whatever you want. You have to begin with the basics, like drawing objects in the room or creating color wheels. After you spend months (or years) learning those basics, only then are you allowed to cut loose. Think of Pablo Picasso, classically trained and then gradually breaking every rule he’d been taught to create something new and innovative. He created his own unique and recognizable style, but only after he knew the rules. The same applies to grammar.

That doesn’t mean you can break whatever rules you want. Picasso’s breaking of the rules was intentional and held meaning. Your choice to break or bend grammar rules has to be the same. There must be motivation and reason behind each rule you break, and, most of all, your work should still be understandable. Here’s an example of an intentional, but still readable, destruction of grammar for style:

It was happening again. He could feel it under his skin, the hair twitching and growing in every pore, his bones breaking and contorting. A strangled scream ripped at his throat. It hurt. It hurt it hurt it hurt it hurt. The moon was bright. A million receptors popped into existence as his nose stretched toward the sky and he could smell everything: Rats in the attic, bread in his neighbor’s oven, the sweaty child with a fever two blocks away, the owner of the local candy shop on Brisbane Alley covered in sugar as he stretched and pulled taffy in the cooler after the shop had closed, his sweat as he pulled and pulled and pulled at the sugared treat in the backroom, another batch another pull more sugar he could smell him he could hear the rush of blood in the owner’s veins he could taste him on the air oh he was hungry. So hungry! The Hunger was all he could think of as he slipped into the shadowed street, musk and fur and hunger to feed.

There are quite a few grammar rules broken there purposefully. This time, the run-on sentences feed into the werewolf’s metamorphosis, emphasizing the change in perspective. It feels hurried and confused because it is. The rule-breakers are surrounded by correct grammar, and short sentences around the run-ons add a resting point for the reader to catch their breath. Still, there’s very little chance we would read a whole book done in the above stylization. After a while, the run-ons would become a chore instead of a nice stylistic trick.

Most rules broken in the name of style are more subtle than the above– a lack of comma here, a super-complex sentence there. These rules are done in service of the writer’s unique voice, usually so that you read a section with the emphasis the writer intended. For instance, I use em-dashes way too much. Incorrectly, sometimes. Does that stop me? No, because even if I use them incorrectly, they’re not so incorrect that you don’t understand what I’m saying. They become a slight nudge towards something I want to highlight or a pause before I say something only tangentially related. You can break rules on purpose this way, but don’t break them so hard that people notice. That is the delicate dance between grammar and intent.

None of us are born creating late Picasso pieces. The great Bag of Writing Rules that contains the entire grammatical structure of language can’t be ignored. This is the one writing “rule” I will say is required. You must learn how language works and why before you can break it. Take the time to learn about where to put commas. Make room in your life for grammar checkers. Just don’t become beholden to them– let an unnecessary em-dash or two slip in. Break a few rules and allow yourself to Picasso your work’s grammar. So long as your audience can read it, you’ve won.