Tea’s journey from budding leaf to the sachet in your cup is a long, deceptively simple one. Every tea is made from one plant, the Camellia sinensis, and thousands of tiny decisions affect the type, quality, tastes, and blends. This ends up giving us hundreds of different kinds of tea. So what are these decisions? And how do they change what ends up in your cup?

Camellia sinensis is a lot like the Vitis vinifera, the common grapevine. Not genetically of course (though who knows- humans share 60% of our genetic makeup with bananas), but in how they’ve been harnessed to create a wide variety of drinks from one single plant. Vitis vinifera makes nearly every wine you can think of- red, white, or otherwise. It’s the way the plant is grown and processed that gives us those varieties. The same is true for Camellia sinensis, the tea tree.

The Camellia sinensis is an evergreen shrub that grows natively in Southeast Asia. In the wild, it can grow between 20 and 98 feet tall, large enough to create bark and make it a tree. On most tea farms, though, the tea plant is often kept at about waist height for easy picking. They are planted in long rows, with just enough space for either humans to walk through, or mechanical harvesters to drive through. The difference in how the leaves are picked at this stage correlates to their end-product quality.

Above is an illustration of a tea branch. At the very end is a bud (in this case hiding behind the flower or nestled in the offshoots) where a new leaf is beginning to grow and the subsequent leaves climb down the rest of the branch. Which leaves, and how they are harvested, can change the taste of the tea you drink. Teas made from the bud at the top of the branch have the most delicate flavors and are used for the highest quality teas. The amount of leaves picked with the bud determines the quality of the flush (the grouping of the leaves picked). For the highest quality teas, only the bud and first two leaves will be harvested, as the youngest leaves are where all the Taste Good Chemicals reside. The further down you go, into the third, fourth, or even fifth leaves, the lower the quality of the tea will be.

Picking a certain amount of leaves off a branch can only be done accurately by human hands. This doesn’t always jive with capitalism though, so mechanical means have been developed to speed the picking process along. As with any shortcuts, there is a dip in quality- mechanical harvesting brings in a lot of leaves (even down to the fifth leaf or lower) but it also brings in a bunch of stems and debris. While a good chunk of the non-tea stuff can be sorted out later in the processing stage, it’s not perfect. Mechanical harvesting is typically done for mass-produced tea bags, like Lipton or Bigelow. Handpicking, or a combination (some cool-looking shears make handpicking quicker), is often used for loose leaf teas.

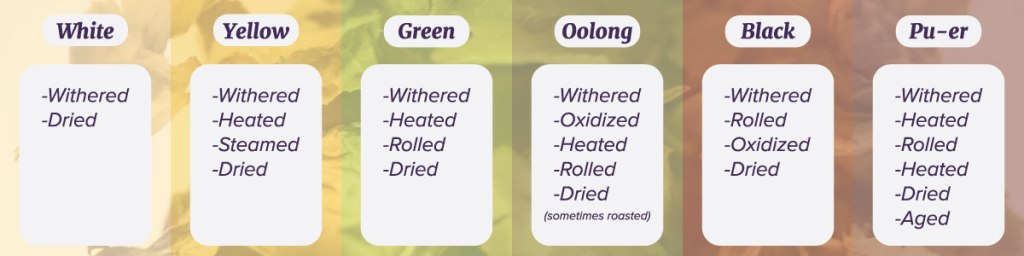

Once the leaves have been harvested and sorted according to which tea they will be used for, they’re ready to be processed. The first step for any tea is withering- letting the leaves dry out on bamboo mats outside or in a humidity-controlled room. Letting the leaves dry out lets the chlorophyll begin to break down and lowers the moisture content to make the leaves easier to handle. White teas are done after this process. The moisture level is brought down in a heated dryer to make the teas safe to be packaged and shipped. This adds a level of prestige to white tea, as the leaf should be able to stand on its own in regard to flavor and aroma.

For all other teas, though, there is additional processing, most of which involve oxidation. Oxidation is what happens when the walls of the plant cells break down and are exposed to oxygen. A bunch of enzymes react to that oxygen and dry the leaf out, turn it brown, and make a bunch of the Taste Good Chemicals jump around all excited (can you tell I’m not a biologist?). Some teas have very low oxidation, like green and yellow teas. Others, like oolongs, blacks, and pu-er, undergo much more oxidation, often involving the rolling and bruising of the leaves to help break down the cell walls and release aromas. Most oxidation, regardless of tea quality, has been mechanized. The leaves are thrown into what looks like a big bingo machine and spun, entering the Tea Leaf Mosh Pit, until they are appropriately bruised and sweaty. There are other machines as well, especially for teabag production, that will rip and tear the leaves.

Once the leaves have been oxidized to the desired amount, they are heated to stop the oxidation process, much like the white teas mentioned earlier. After the heating, the leaves are dried to the desired moisture level for packaging and sorted. Before they’re shipped they can also undergo firing (if it’s a roasted tea) or fermentation.

Pu-er teas are special in that they’re very similar to wine: they’re fermented and aged. After going through most of the same process as other teas, they are then dampened and shaped into bricks or disks, compressed, and placed in a dark temperature-controlled room to dry out and age. This ferments the tea, lending it a flavor you can only achieve by aging. Most pu-ers are aged at least ten years, though sometimes up to fifty! There have been attempts at speeding up the process by using higher temperatures and humidity levels but, much like wine, artificial aging doesn’t taste the same. However, it is a much more accessible price for those wanting to try pu-er but unable to afford the good stuff.

With all the processing done, the leaves get shipped out to the market, ready for consumers to press their noses into tins and buy a twenty-pack of teabags. Keen readers may notice that while I’ve described the process for different types of tea (white, green, black, etc.) I didn’t explain the different varieties. After all, you don’t go to a store and just buy “Black Tea”. You have so many options, from Earl Gray to Darjeeling to Golden Monkey! So how do varieties get made? Well, you’ll have to tune in next month when I go over cultivars, terroirs, and post-tea processing. Until then, happy sipping!

If you'd like to dive into tea production more, check out the resources I used below: Discovery UK, Tea | How It's Made Kevin Gascoyne, Francois Marchand, Jasmin Desharnais and Hugo Americi, Tea: History, Terroirs, Varieties, First Edition (While the first edition is no longer for sale, updated editions may be found at your local bookstore or places like Barnes & Noble)

2 thoughts on “From Leaf to Cup: Part 1”